Wagashi

Filling

Gift Set

Filed under: Food, Image | Tagged: Wagashi | Comments Off on Japanese Traditional Sweets for Father’s Day

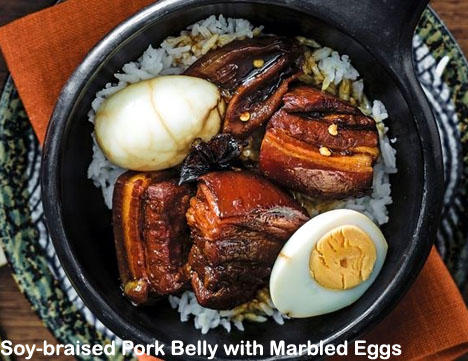

Ingredients

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 kg boneless pork belly, cut into 6- x 3-cm pieces

6 cloves garlic

6 shallots

4-cm piece ginger, thinly sliced

1 long red chili, halved lengthwise

2 star anise

1 teaspoon Chinese five-spice

1 cup sweet soy sauce

1/2 cup light soy sauce

coconut water of 1 young coconut

8 eggs

steamed rice and lime wedges, to serve

Method

Makes 8 servings.

Source: Taste magazine

Filed under: Asian, Braise, Herb, Pork, Recipe Clipping, Rice | Comments Off on Indonesian-style Braised Pork Belly with Sweet Soy Sauce

Deena Shanker wrote . . . . . .

Farmed or wild? Local or imported? Organic? Or some certification you’ve never heard of?

Anyone who has tried to be an eco-conscious seafood consumer—or seen headlines about plummeting wild fish stocks or antibiotic-laden seafood from farms in China—has faced these questions.

There are many more. Take farms, whether inland or in the ocean. So much depends on the particular operation. Are antibiotics used to fight disease in overcrowded pens? What’s the feed made from, and is too much provided? How much waste do the fish create? Are the currents strong enough to disperse all of that? What is the ocean floor like? Are the fish native?

“With fish, people come in and debate,” said TJ Tate, director of the Sustainable Seafood Program at the National Aquarium in Baltimore. “Consumers want to see a tag, a label, a box, something they can feel confident about, and grab it and go.”

“A lot of labels are private or secretive or changing or flexible,” said Marianne Cufone, executive director of the Recirculating Farms Coalition. Some are more respected than others, and it’s hard for the average consumer to know the difference. While Canada and the EU have organic seafood standards, the U.S. does not.

Now, entrepreneurs, investors, and some environmentalists are beginning to coalesce around aquaculture as a potential long-term solution to the depletion of the oceans and the world’s increasing appetite for this healthy protein. A 2016 report from the United Nations found that 31.4% percent of the world’s stocks were overfished and another 58.1% fully fished. Meanwhile, aquaculture surpassed wild-caught fish as a source of seafood for human consumption in 2014. Many see it as the next frontier in sustainable food production.

“We’re eating more seafood globally, which is a good thing because it’s healthy, but we’re taking more than the ocean can naturally replenish,” said Amy Novogratz, managing partner of Aqua-Spark, a Netherlands-based investment fund focused on sustainable aquaculture businesses. “Aquaculture is known a little bit for its bad reputation, and some of it is deserved,” she said, referring to issues like China’s use of antibiotics and fish feed made from wild-caught species. “But it’s a young enough industry that you can go in and rebuild it a little, so as it grows, it grows more sustainably.”

Aqua-Spark invests all along the aquaculture supply chain, from Calysta, a Menlo Park, California, company making feed from methane-eating microbes, to eFishery, a developer of feed delivery machinery in Indonesia, to Matorka, an Icelandic land-based Arctic char farm, and one of its latest portfolio additions, Love the Wild, of Boulder, Colorado.

Love the Wild sells frozen, single-serving, boxed fish filets that come with sauce, parchment paper, and cooking instructions, so user-friendly that even a novice in the kitchen could make them. Each box includes the name of the farm, its location, managing partner, and any certifications it has earned. In March of 2016, the products were available in only two stores in Colorado. Now they’re sold in nearly 700 stores in 33 states, at major retailers like Whole Foods, Wegmans, and Price Chopper, as well as smaller single stores and co-ops. Leonardo DiCaprio has signed on as an investor and advisory board member.

The company offers five products, each a different species from a sustainable fish farm, like Barramundi with Mango Sriracha Chutney, and Catfish with Cajun Creme. The barramundi is raised in an open ocean net pen in Vietnam, while the catfish comes from pond systems in Alabama and North Carolina. The farms are scattered around the world and use different systems and technologies, but they have a similar ethos. And while Chief Executive Jacqueline Claudia is proud of the sustainable practices each employs, she admits there is plenty of room for improvement. “We’ll never feel our products are sustainable enough,” she said.

On top of rigorous third-party audits, Claudia visits each farm frequently to make sure it is living up to her standards—for example, that the feed minimizes the use of primary-catch wild fish to avoid taking them out of the ocean, and that the fish meals the farms do use come from processing waste that would otherwise be used as fertilizer anyway or end up as garbage. The company is actively working to reduce reliance on marine proteins, using soy and other grains instead. “We want to move towards microbial, insect, and algae-based feeds,” Claudia said.

The company also looks at the aquaculture systems’ management practices, including the way waste is handled, the site of the farm and density of its fish stocks, and the treatment of the workers.

As for escapes, a major problem in open ocean aquaculture, some are inevitable. Predators, like sharks and seals, will try to chew through the pens, oceans are unpredictable, and human error is a risk. The strategy is to minimize the impact they can have.

“Pen technology should be suitable for the area where it’s located. Sometimes that means double or triple layer,” Claudia said. “And we only work with species that are considered native or indigenous to the area where they’re raised. If one gets out, it’s not introducing something new.” Love the Wild’s catfish is raised in ponds and its trout in raceways, artificial channels that have a continuous source of water flowing through them.

“Jacqueline is very detail-oriented,” said Tate, of the National Aquarium, who endorses Love the Wild, and has no financial interest in it.

Proponents of land-based aquaculture systems say these can be a better option because there is no escape risk or waste discharged into the oceans. “Water is constantly being recirculated in our systems, so there is no waste runoff,” said Cufone, of the Recirculating Farms Coalition. Claudia says her inland farms also have no waste runoff—the ponds are contained with a clay bottom and the raceways use a filtration system that cleans the water before it is discharged into the river.

“We worry about open ocean aquaculture,” said Patty Lovera, assistant director of Food & Water Watch, a consumer and environmental advocacy group. “It depends on how big and where. A huge question is what you feed those fish.” She added, “It’s hard to know unless you’re going to get on a boat and go out and look at it.”

Other environmentalists see an opportunity in open ocean aquaculture, even if it isn’t risk-free. “Whether from terrestrial plants or animals, the production of protein will use land, freshwater, and energy,” said Aaron McNevin, director of markets and foods at the World Wildlife Fund. “The open oceans represent a very remote area with the ability to naturally process wastes in the vast waters much beyond the capacity of our freshwater systems to process agricultural runoff.”

Wild fish don’t need to come off the menu—it just depends on the fishery. Alaskan salmon and porgy from the East Coast, among others, are good choices. Buy from, and talk to, your local fishmonger, said Cufone. Expand your seafood horizons beyond salmon, tuna and shrimp, said Lovera.

And, Tate advises, if all you know is the country of origin, buy American.

“If it’s raised, harvested, or caught in America, you should feel good about it, because we have the best management systems from wild to aquaculture, bar none,” she said. “So if it says farmed in the USA, you’re good, buy it.”

Source : Bloomberg

Filed under: Food, News and Articles | Tagged: Fish, Future | Comments Off on How We’ll Eat Fish in the Future

Recreational runners are less likely to experience knee and hip osteoarthritis compared to sedentary individuals and competitive runners, according to a new study published in the June issue of the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy® (JOSPT®).

The study concludes that running at a recreational level for up to 15 years–and possibly more–may be safely recommended as a general health exercise. Further, the evidence suggests recreational running may have benefits for hip and knee joint health.

An international team of researchers in Spain, Sweden, the United States, and Canada aimed to evaluate the association of hip and knee osteoarthritis with running and to explore the influence of running intensity and years of exposure on that association. They found in their systematic review of several studies investigating the relationship between running and arthritis of these weight-bearing joints that only 3.5% of recreational runners developed hip or knee arthritis. This was true for both male and female runners.

Their findings further indicate that remaining sedentary and forgoing running for exercise was associated with a rate of knee and hip arthritis of 10.2%, while training and running competitively increases the incidence of arthritis in these joints to 13.3%. The study’s authors note that other researchers who have also found a link between high-volume and high-intensity runners and knee and hip arthritis define exercise at this level as running more than 57 miles (92 km) per week.

“The principal finding in this study is that, in general, running is not associated with osteoarthritis,” says lead author Eduard Alentorn-Geli, MD, MSc, PhD, with Fundación García-Cugat; Artroscopia GC, Hospital Quirón; and Mutualidad Catalana de Futbolistas-Delegación Cataluña, Federación Española de Fútbol in Barcelona, Spain, as well as the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN. He adds that “the novel finding in our investigation is the increased association between running and arthritis in competitive, but not in recreational, runners.”

Dr. Alentorn-Geli and his fellow researchers used PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases to identify studies investigating the occurrence of osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee among runners. They reviewed 25 studies that included 125,810 people, and ultimately selected 17 studies involving a total of 114,829 people.

The study’s authors then conducted a meta-analysis of studies, comparing this occurrence between runners and sedentary individuals who did not run. Runners were considered “competitive” if they were identified themselves as professional/elite athletes or participated in international competitions. Recreational runners were those individuals who ran in a nonprofessional, or amateur, context.

The researchers calculated the prevalence rate and odds ratio (with 95% confidence interval [CI]) for osteoarthritis between runners at both competitive and recreational levels and sedentary individuals. They also performed subgroup analyses for arthritis location (hip or knee), gender, and years of exposure to running (less or more than 15 years).

Dr. Alentorn-Geli and his colleagues were not able to determine the amount of running that is safe for these joints. The study’s authors also caution that they did not assess the impact of obesity, occupational workload, or prior injury on the future risk of hip and knee arthritis in runners.

Source: EurekAlert!

Filed under: Exercise, News and Articles | Tagged: Osteroarthtitis | Comments Off on Recreational Running Benefits Hip and Knee Joint Health